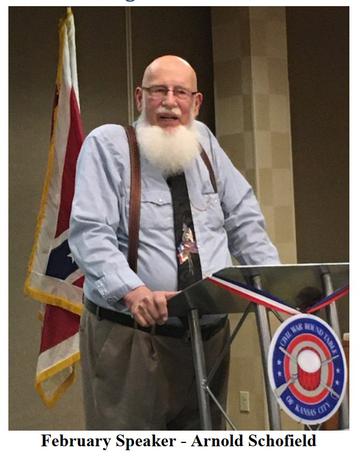

February 2020 Meeting

At our dinner meeting on February 25th, Arnold Schofield gave a very interesting presentation about the myth of African-American soldiers fighting for the Confederacy. Arnold's program was based on the book titled: Searching for Black Confederates, The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth. This book was written by Mr. Kevin M. Levin and published in 2019 by the University of North Carolina Press. Attendance at the February dinner meeting totaled 55. Arnold made the following points during his presentation:

- Arnold said he got interested in black military history 40 years ago. Based on his research, the existence of black Confederate soldiers is a myth. A myth is interesting, but for the most part, a myth is fictional. A myth that is carried on year after year eventually becomes a legend.

- In 1861, there were 4 million slaves in the Confederate states. The majority of the slaves worked in the agricultural force, as field hands on Southern plantations. The balance worked in the industrial/commercial labor force of the Confederacy. If not for their involvement, the industrial/commercial labor force would not have been adequate to support the Confederacy.

- During the Civil War, 200,000 African-Americans served in the military forces of the United States. 180,000 served in the army and 20,000 served in the navy. These men were former slaves, escaped slaves, and free blacks.

- There was a social caste system regarding slaves in the South. Field hands were the lowest level. Next were the tradesmen: blacksmiths, stonemasons, coopers, and wheelwrights. Above them were the domestic servants: butlers and servants that worked in the home. At the highest level were the personal servants.

- The industrial/commercial workforce consisted of ironworkers, foundry workers, teamsters, section gangs on the railroads, crews on waterways and steamboats, etc. Ninety percent of the industrial/commercial labor force in the South was African-Americans.

- The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond VA bought slaves to work in the ironworks and the iron furnaces in the Shenandoah Valley. Tredegar's labor force consisted of 4,000 African-Americans and 500 whites.

- At the iron furnaces, all men were well-trained. Typically, there would be 300 to 500 slaves and less than 50 managers. The majority of the slaves were hired out or rented by their owners. This was especially true of the tradespeople. Blacksmiths could earn $50 per month. The slaves' owners got to keep the money. The logistical support given to the Confederate war machine was 90 percent African-American.

- At the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy needed earthwork for fortifications. Owners donated slaves in 1861, when patriotic fever was spreading. However, as the war went on, the patriotic fever declined and slaves were rented out and were paid for. The states had quotas. Each state had to supply so many slaves. Owners were reluctant to supply slaves, because they didn't always get paid what they were supposed to get paid for their slaves.

- In 1861, there was a tariff on cotton. No cotton could be exported. The Confederate war machine needed food, so the plantations had to switch from growing cotton to growing com, wheat, beans, potatoes, yams, etc. Asking the same labor force to switch crops was a big problem. All of a sudden, slaves were not coming from plantations or farms. That created problems in the production of war materials.

- The perception of black Confederate soldiers comes from Union officers. In 1862, the Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland during the Antietam campaign. Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, inspector of the United States Sanitary Commission reported that African-Americans seen in Frederick MD were clad in all kinds of different uniforms, Union and Confederate. Steiner noticed that these blacks carried rifles, muskets, sabers, and other weapons. That description is a classic description used to describe African-Americans serving in the Confederate army. However, these men were not soldiers, they were camp slaves or body servants. The African-Americans marching behind the Confederate army were carrying weapons, cook pots, etc. They made then-owner's job easier. The slaves carried the weapons of their owners. Muskets were not light.

- At the beginning of the Civil War there was a lot of sickness (dysentery, diarrhea, etc.) because food was not cooked properly or long enough. Regulations were issued and each company was authorized to carry two cooks to cook the food. The cooks were typically African-American slaves. They were recorded as civilian cooks and as slaves. They performed a number of duties such as brushing uniforms, polishing swords and buttons, cooking, grooming or caring for horses, etc.

- The camp slaves did not desert for several reasons. One reason is because they were loyal to the officers that bought the slaves. Also, they were loyal to their families back home. If a slave deserted, they might not ever see their family again.

- After the Civil War and up to the 1890's there were no accounts written about black soldiers or black veterans. They were camp slaves and not soldiers. In 1890, veteran organizations such as the United Confederate Veterans started having reunions. African-Americans started attending these reunions. These men were camp slaves that were loyal to the Southern cause. They attended these reunions up until the 1920's.

- In 1890, former slaves started applying for slave pensions of $10-$ 13 per month. They submitted different application forms than soldiers did. If the pension application was approved, they were denoted as a camp slave or personal slave.

- There is an iconic photograph of Confederate sergeant Andrew M. Chandler of the 44th Mississippi, Company F and his camp slave Silas Chandler, who are dressed in Confederate uniforms. After Andrew was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863, Silas brought him back home. Silas died in 1919 at the age of 82. In 1994, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed an iron cross on Silas' grave in recognition of his Civil War service. Silas' great-granddaughter removed the iron cross later because she thought it was used to perpetuate a myth.

- The Louisiana Native Home Guards was a black unit that was organized in 1862, in order to protect New Orleans. However, the governor of Louisiana refused to accept them. When Union forces under General Benjamin Butler occupied New Orleans, he took three regiments of the Louisiana Native Home Guards and used them to defend New Orleans against the Confederates.

- Based on his 40 years of research, Arnold said there is a definite lack of documentation and evidence of black soldiers fighting for the Confederacy, either individually or as a unit. It is a myth that there were 6,000 to 10,000 African-American soldiers in the Confederate forces. Arnold said the myth will continue as long as people believe that they did.

- Thousands of blacks served in the Confederacy, but they were cooks, teamsters, etc. There is no documentation that they were soldiers. They were not awarded pensions as soldiers. In the North, African-Americans enlisted as black soldiers and fought in combat.

- Headstones on Confederate graves in North and South Carolina may show the names of camp slaves. However, the regiment and company designations are those of the slaves' owners.

|

| |